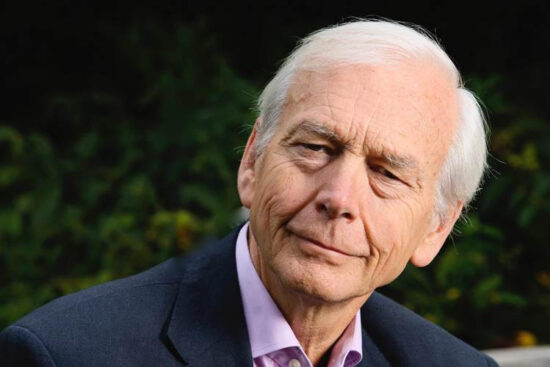

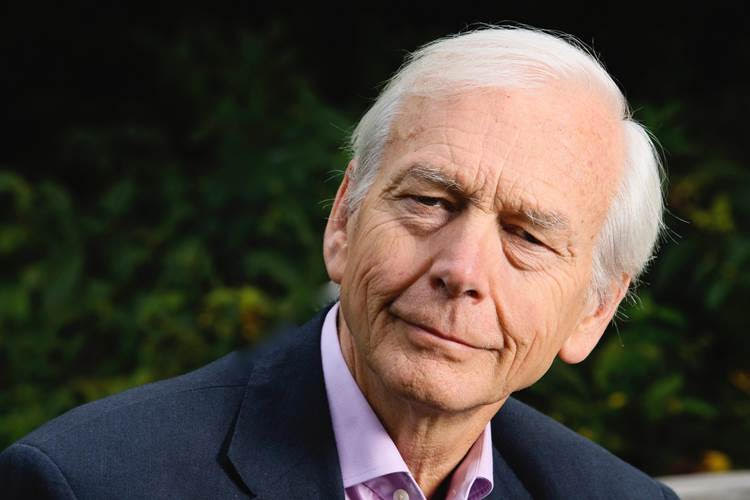

An unsentimental trip down memory lane for John Humphrys, broadcaster, journalist, and former presenter of BBC TV’s ‘Mastermind’.

Ah… the smells of childhood. Twice a week the bread baking gently in the oven. On Sunday mornings the promise of the slowly roasting leg of lamb. In summer fresh strawberries. And every evening the joy of bed-time cuddles with my sweet-smelling mother.

So much for the dream. The reality?

My own mother was about as likely to bake bread as she was to settle down with Proust while the butler uncorked the ’47 Chateau Laffite. A sporadic income, five kids and no little luxuries such as vacuum cleaners or washing machines does not permit leisure. And anyway, I never saw her read. Ever.

The fruit was only what was in season: preferably the apples we kids stole on forays into the posh areas of Cardiff where they had gardens and walls you could climb over. We weren’t often caught. Our meat was mostly the scrag end of neck. Cheap and delicious after many, many hours of boiling and a lovely smell.

But it was the rather less lovely smells by which my childhood was defined.

My mother was a hairdresser and she did the neighbours’ haircuts and perms. It didn’t exactly pay for fine wine but it helped. The drawback was the ammonia stench from the perm lotion – as harmful as it was unpleasant. I’m convinced it destroyed Mam’s lungs over the years and contributed to her early death.

Sometimes the perm smell was overpowered by the fumes from the acid crystals my father boiled in a baked beans tin on the stove. He needed it because he was a French polisher and the standard ‘stripper’ was sometimes not powerful enough to return the wood to its original colour. It, too, was vile and probably even more harmful.

The kitchen was not just where my parents worked, it was also where we washed, ate and lived. It could have done with being a bit bigger – especially when Dad had a piano to polish. He dealt with it by dismantling it, polishing every single individual bit (try counting them) and assembling them again after they’d been stripped of their old polish and re-polished. I think multi-skilled was an appropriate description for him.

Multi-skilled and tough.

He’d been blind when he was a small boy. Measles damaged his optic nerve when he escaped from the house to throw snowballs one sunny winter’s day and his sight never fully recovered. It stopped him driving but it didn’t stop him working. He used Mam’s eyes to tell him if he’d got the colours right. Nor did it stop him running. His proudest possession was a bronze medal he’d won in the county athletics championships. A friend told me he’d once run off the track into the barbed wire bordering it but kept going. He always did.

He was self-employed because he’d been sacked from his job after completing his apprenticeship. At the end of his first week he punched the foreman on the nose. He was never employed again.

Dad was a Tory, which was odd. He hated trade unions but hated the upper class and the monarchy more. If he was told to use the servants’ entrance when he showed up to do a job at a very posh house he would walk away. He was the only person in our street who didn’t go to watch the Queen drive by when she visited Cardiff. And he walked out of the Tory club when he showed up one night and the only vacant seat was beneath the obligatory portrait of the Queen. He refused to sit in it and was thrown out. He never went back.

Christine was my little sister. My big sister Anne worshipped her. She was her baby.

I learned that something bad had happened to her on a Friday: a special day because we were sometimes allowed fish and chips from the chip shop for dinner. Not ‘lunch’. Only the posh had ‘lunch’. I had been sent to the chip shop and when I got back a car was parked outside our house. A vanishingly rare sight. It was the doctor’s.

He had come to tell my parents that Christine was dead. I missed his announcement by a few minutes. And anyway, at the age of five, death isn’t really something you can grasp. Is it ever?

What puzzled me was that nobody showed any interest in the fish and chips, and they were growing cold. And that my mother’s lovely black hair went white almost literally overnight.

Had I been old enough I would have been outraged that my parents were not at Christine’s bedside to hold her hand when she breathed her last. She’d had gastroenteritis, which was not a killer disease but obviously something had gone horribly wrong with her treatment. Yet the hospital had not thought to tell my parents that she was critically ill and they would be allowed to see her outside the official visiting hour.

You’ll have gathered by now that I have always deeply resented our poverty and, call me pathetic, I resent it still. Those who talk about its so-called ‘dignity’ should be dealt with the way my father dealt with his foreman. The dignity of poverty is a myth and always has been. It is at best degrading and at worst brutal.

Not that my father would have accepted what he regarded as charity from the state. Many of our neighbours – some of them even worse off than we were – would receive frequent visits from ‘the man from the welfare’ with his clipboard and sneer (real or imagined) but he was never allowed to cross our threshold.

I remember one neighbour – a war widow – telling my mother he’d read her the riot act for wasting money. He’d spotted four chairs at her kitchen table even though she had only two kids, so she needed only three.

Dad gave me my first (unpaid) job when I was ten: pushing leaflets through the letterboxes of posh houses advertising his availability as a French polisher.

But there was light in this gloom. Perhaps because they’d had virtually none for themselves, my parents understood that education mattered and Mam made us kids do homework. Every night. And it paid off when we sat the eleven-plus. I managed to get into the best grammar school in Cardiff. I hated it. Largely because it was boys only and very posh (we were required to doff our caps to ladies in the street) and I was the poorest kid in my year. The head, George Diamond, seemed not to like poor kids.

He once beat me for being late – even though I explained that I’d had to do my usual paper round before school and the man who delivered the papers to the shop had been delayed getting to the shop because of heavy snow overnight. He was not impressed when I told him we needed the money I earned.

I left school at fifteen and got my very modest revenge on him a few years later when the school invited me to make the speech at the annual prizegiving day. By then I had a modicum of fame because I was on the telly. I wrote back accepting the invitation and, helpfully, outlined what I planned to say about Mr Diamond in my speech. The invitation was withdrawn.

Holidays were rare and brief: perhaps a week in a boarding house. Maybe not. As for going abroad: unthinkable.

But when I was posted to New York by the BBC and earning lots of money I brought my parents out to stay and then, years later when I was in South Africa, I took them there too.

Even before they landed they had been struck dumb.

Because of apartheid sanctions passengers flying to Johannesburg had to switch to South African Airways in Rhodesia, South Africa’s only friend in the region. A jumbo jet was waiting – the first my parents had ever seen. It was almost empty and the lovely crew insisted they move into first class. They had it to themselves. They never stopped talking about it.

But their trips almost got them into big trouble. I learned about it from my mother’s closest friend many years later.

Because he was self-employed, Dad obviously had to send in a tax return every year telling the Inland Revenue how much he had earned. He was a scrupulously honest man and all was fine until the day he and Mam (who kept his books) were summoned before an inspector. The great man sat behind his large desk, my parents in front of him on hard-backed chairs. There were no pleasantries.

“Is this really the total of your earnings?” he barked.

“Yes”.

“But we are informed you have been making hugely expensive foreign trips. Explain!”

My usually timid mother stood up.

“Our son is John Humphrys, the one on the television, and he paid for them!”

She told her friend later it was the proudest moment of her life. I hope she knew it was she who she made it possible.

Thank you John for sharing your memories with us.

Splott’s rich heritage is being celebrated in a ‘pocket museum’ telling ‘The Story of Splott in 50 objects’.

The museum consists of a deck of cards with each card telling a different part of the Splott story, its events, people, places, or things. A crowdfunding campaign will be launched this Friday to support its printing and the pocket museum will be available at various community venues.

Please visit https://shorturl.at/oWAXy to find out more and have your say, or email any ideas to hello@inksplott.co.uk

Whether it is inspiring stories like John Humphrys’, or unusual and curious bits of your history, we’re creating a treasure trove of local heritage. Do find out more.

*The Story of Splott is a partnership project between Grow Social Capital, Splott Community Volunteers and More in Common.

Splott Community Volunteers is a non-profit organization helping to make Splott a better, happier place, running a range of support activities including Breakfast Clubs, community events, and providing volunteering opportunities.

Cardiff-based Grow Social Capital is a social enterprise working to promote greater use of the power within communities, through their shared identities, stories, and relationships to overcome adversity, build togetherness, and create positive narratives of their future.

More in Common was founded in the aftermath of the tragic murder of Jo Cox MP in 2016, taking its name from Jo’s maiden speech in Parliament where she said: “We are far more united and have far more in common than that which divides us.” Its network consists of community groups and partnerships of larger organisations that work to bridge divides and positively contribute to strengthen social cohesion.